What’s there?

An exposition (I love this word sm) into techniques of Inverse Transform Sampling and the algebra of random variables.

Why do I write this?

I wanted to create an authoritative document I could refer to for later. Thought that I might as well make it public (build in public, serve society and that sort of stuff).

Inverse Transform Sampling

This is how you generate random samples from any probability distribution.

Foundations

Y’know the standard uniform distribution, . This is a continuous distribution where every value in the interval

is equally likely.

We assume the existence of a pseudorandom number generator (PRNG) that can produce such samples.

Imma also just recap the properties of the CDF ()

- It is a non-decreasing function.

- It is right-continuous.

and

. Tts range is therefore the interval

.

Intuition

A simple observation – if we apply the CDF of a random variable to the variable itself, the resulting random variable

follows a standard uniform distribution,

. The inverse of this statement is the key to the sampling method: if we start with a uniform random variable and apply the inverse CDF, we will generate a random variable with the desired distribution.

So cool.

Theoretical development

Theorem (Probability Integral Transform): Let be a continuous random variable with a strictly monotonic CDF,

. Then the random variable

is uniformly distributed on

.

Proof: We want to find the CDF of , denoted

for

.

Since is a strictly increasing function, its inverse

exists. We can apply it to both sides of the inequality inside the probability expression without changing the direction of the inequality:

By the definition of the CDF of ,

. Therefore:

The CDF of the random variable is

for

. This is the CDF of the standard uniform distribution,

.

Importantly, note the strictly monotonic CDF bit!

Algorithm

- Generate a uniform sample: Draw a random number

from the standard uniform distribution,

.

- Apply the inverse CDF: Compute the value

.

- Result: The resulting value

is a random sample from the distribution with CDF

.

When does this not work?

This requires the CDF to be invertible. What if it isn’t? Example – for Guassians (the most predominant stuff). Update – Advanced Methods for generating RVs

Sums and Products of Random Variables

What do we need to do?

Let and

be two random variables with known distributions. We define a new random variable,

, as a function of them, for example

or

. The goal is to find the probability distribution of

.

Sum of independent RVs

To find the distribution of the sum, we first find its CDF, . This probability is the double integral of the joint density

over the region where

.

Wut. How can we even compute this. Yeah, dw, we use independence and say that their joint density is the product of their marginal densities, .

We also differentiate – since the PDF is the derivative of the CDF (wrt ) This gives us that convolution formula!

(I derive the product one properly to give better understanding, btw.)

Important Special Cases:

- Sum of Gaussians: The sum of two independent Gaussian random variables is also a Gaussian. If

and

, then

. This is a rare case where the convolution has a simple, closed-form solution.

- Sum of Poissons: The sum of two independent Poisson random variables is also a Poisson. If

and

, then

.

Product of independent RVs

Define the product

The CDF of , denoted

, is the probability that

is less than or equal to some value

.

Since and

are independent, we can express this probability as a double integral of their joint density,

, over the region where

.

To make this integral solvable, we need to set explicit limits. The inequality or

depends on the sign of

. We must split the integral into two parts: one for

and one for

.

Define the CDF properly

- When

, the condition is

.

- When

, the condition is

.

This allows us to rewrite the CDF as:

We can express the inner integrals in terms of the CDF of , which is

.

Find the PDF

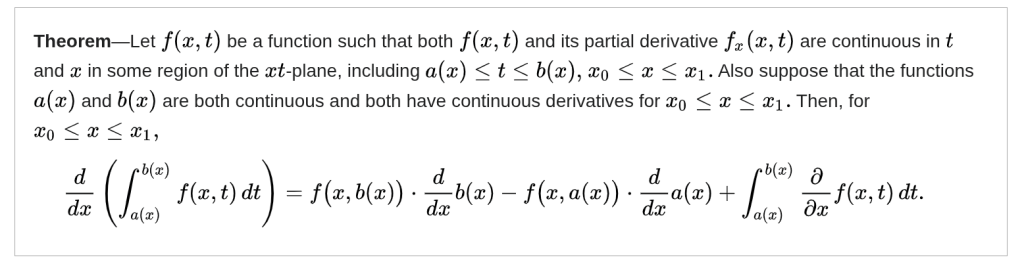

The PDF, , is the derivative of the CDF with respect to

. We can differentiate under the integral sign using the Leibniz integral rule.

Using the chain rule, the derivative of with respect to

is:

Substituting this back into our expression:

For the first integral, , so

. For the second integral,

, so

. Since both integrands are now identical, we can combine the two integrals back into one:

Sources

Leave a comment